No wait, of course that is the single most important SaaS

metric

Is it LTV? Retention? NRR? Magic Number? Rule of 40? Or: Do you need to un-ask the question?

Is it LTV? Retention? NRR? Magic Number? Rule of 40? Or: Do you need to un-ask the question.

The single most important SaaS metric is retention

Cancellations indicate lack of Product/Market Fit, no matter the cause (price, features, severity of need, duration of need). If it cannot be fixed, it means the business is a failure even if other metrics are stellar, because it means customers are rejecting the product. Once you’re scaling (i.e. past Product/Market Fit and into tens of millions in revenue), you realize that cancellation scales exponentially with total customers—whereas new-customer growth scales linearly with sales and marketing costs—which means cancellation necessarily and always outgrows inbound activity, thus growth ceases. So, retention is most-important, regardless of stage.

The single most important SaaS metric is top-line growth

High revenue growth implies many other (even un-measurable) things are going well, such as Product/Market Fit, ability to get to customers, ability to retain customers, and proving the large size of the addressable—no really, we’re actually addressing it!—market. High growth is the only way to build a large tech company, because tech market dynamics follow a “winner take all” power law, and the only way to be the biggest is to grow the fastest. Fast growth proves every other piece of the company is healthy, or at least healthy enough not to be fatal. High-growth companies have all the options—staying independent, raising money, selling. It’s also by far the greatest determinant of equity value, because it maximizes both revenue and the revenue-multiple.

The single most important SaaS metric is net-profit growth

The days where equity value is determined almost completely by top-line growth died in 2015, and now both public and private markets are rewarding not just growth, but profitable growth. Which is better anyway, because it means we’re building sustainable, value-creating companies, not just companies that grow like a virus, without purpose and possibly killing the host. The unicorns are dying not for of lack of revenue, but for lack of profit.

The single most important SaaS metric is sales efficiency

If it’s expensive to acquire new revenue, it means the product is being stuffed into the market rather than embraced by it, which means you’re artificially growing rather than having found real Product/Market Fit and longevity. It will be too hard to grow at scale because merely replacing natural cancellation is expensive, thus your maximum size is capped. The expense means it’s too hard to be profitable in the long run, because too much of a customer’s lifetime revenue is spent in costs before they even write the first check. It means you’re “buying customers” rather than building a product people organically want, enjoy, and talk about, which in turn calls into question the fundamental value of the product.

The single most important SaaS metric is LTV

If you look at the component metrics individually you never get a complete picture. High growth is great, but not if margins are so low there won’t be a profitable business at scale. High retention is great, but not if MRR is so low that sizable revenue requires too many customers. When you optimize one number in LTV, often the others change in contrary directions. For example, you can increase price which increases MRR but also increases cancellations as people can’t afford it. Only by combining these metrics can you get a clear and true picture of the health of the business model. Some people say LTV isn’t valid because the future is unpredictable, but that’s exactly why it’s so important to try.

The single most important SaaS metric is the Rule of 40

Either your company needs to be growing fast (in which case being unprofitable now creates long-term value), or your company needs to be very profitable (where generated “value” is literally cash coming out of the business, over many years). The “Rule of 40” achieves this—the sum of YoY revenue growth rate and bottom-line profit margin—the “super-metric” that covers both the “growth” and “profit” phases of a successful company’s lifespan.

The single most important SaaS metric is NPS (customer satisfaction)

This is the ultimate measure of value-creation, which in turn impacts every other important metric. It impacts new growth because only high-NPS customers will propigate word-of-mouth marketing—the least expensive form of marketing and one of the few that continues to scale with the business. It impacts retention because high-NPS implies they’ll stay. It even impacts objectively important things which don’t have numeric metrics, such as brand quality and Product relevancy and customers who love you even when you screw up. It covers not only Product Management but Tech Support and every other function. The customer is the fundamental unit of the company, and NPS measures customer health.

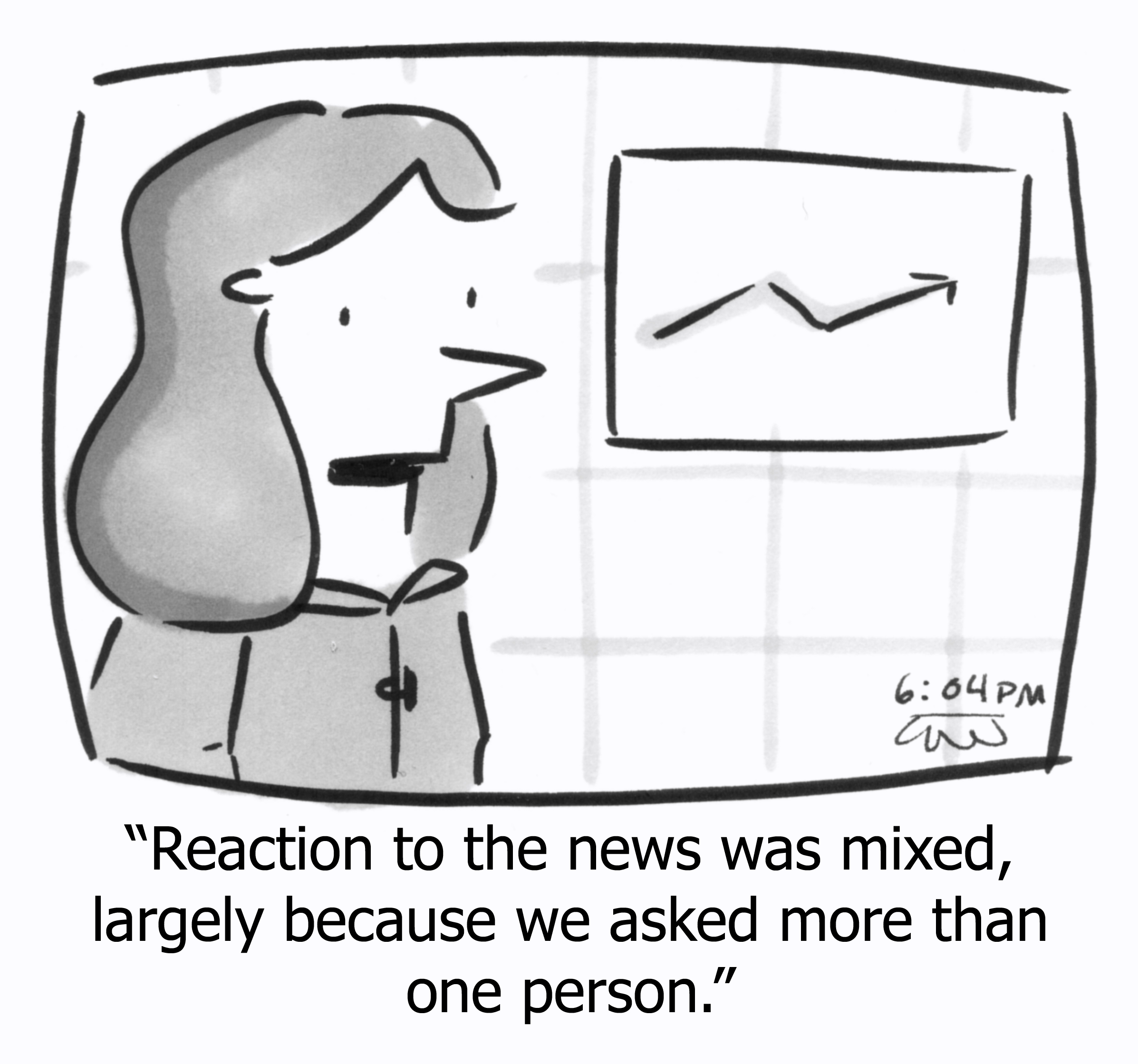

All of these statements are true, for some companies, at some times, in some stages, in some industries, in some markets. But the larger point is that companies are more complex than “a single most important metric.”

The purpose of a metric is to be a tool in service of your goals, timeline, size, circumstance, even philosophy, not a master you that you thoughtlessly obey.

Focusing on just one thing is valuable because it creates focus, especially when a company is young and there isn’t enough time to maximize multiple goals. Larger companies like WP Engine can have three or four, but still not many.

Your job is to figure out what’s most important right now, what’s on fire, what’s most important for getting the company to its next milestone, lean into what’s working well, and then simplify and clarify the few goals and metrics that your entire company should align on. Like this.

This article was originally published here.

"Great article! Must read blog for entrepreneurs who wish to start business with SaaS Platform. The explanation provided about various SaaS metrics and their importance is simply excellent."

Interesting blog

This is a fantastic breakdown of the various SaaS metrics and their importance. It's a reminder that while each metric has its value, a holistic approach is essential for long-term success.