The definitive product positioning framework (part

one)

Anthony Pierri on how to choose your target customer segment.

Before we can talk about the process of building your positioning strategy (and actualizing it on your homepage), we need to define some terms.

When we say “positioning,” we actually mean “product positioning.”

Product positioning contains two strategic choices:

Who are you going to target?

How will you differentiate?

As you’ll quickly realize, different customer segments use your product for different reasons… and each will need their own positioning strategies.

Product positioning ≠ brand positioning.

Brand positioning on the other hand is more concerned with the commonalities across all segments, use cases, etc. It includes making decisions about your vision, purpose, personality, emotional connections you wish to create, and any other important associations you seek to foster with customers.

Both types of positioning have their place in the overall company strategy, but for our purposes, we’ll be focusing on product positioning.

It’s a strategic bet, not a quickly testable hypothesis.

Because we argue that the above-the-fold section of a homepage should house your positioning, people often believe that positioning can be tested and optimized using standard conversion-rate techniques.

They look at heat maps, run A/B tests, and do quantitative and qualitative surveys on the homepage to “test” or “measure” their positioning.

While totally understandable, this is a misguided approach.

Take this one small example:

Should you position for enterprise?

Or should you position for SMB?

Imagine you were trying to decide which would be a better focus for your company… by running an A/B test with two different website hero messages—one for enterprise, one for SMB.

In case it doesn’t become immediately apparent why this would be unwise, let me walk it out:

Which segment converts better on a homepage is a terrible indicator of which segment is better overall for your company.

The product requirements for enterprise companies couldn’t be more different than the requirements of SMB.

The go-to-market strategies of each are world’s apart, along with the ways you monetize those deals, the level of customer support expected, the amount of competition, etc.

Not to mention if your GTM efforts up to this point have been aimed at SMB, then your enterprise messaging will flop (because likely no enterprise clients are even viewing your website in the first place).

This is just one vector of positioning that impacts essentially every part of how you operate your business. And there are an infinite number of related decisions you could make when positioning your product with an equally staggering number of cascading impacts on every department in your org.

Positioning (unfortunately) is not something you can test in an afternoon. There’s no A/B test to determine positioning. Data can help inform your decision, but ultimately you need to make the call of where you will focus.

The better way to think of positioning is placing a strategic bet — i.e. making a choice to focus on one group rather than another, to compare yourself to one set of competitive alternatives rather than others, and then to build differentiation for that specific context.

Positioning comes before messaging.

On the flip side, once you’ve made the decision about whom to target and how you will differentiate, you can test how you frame these choices.

The way you express these decisions in different assets is called “messaging.” For example, do you lead with the problem? Do you lead with the outcome? Do you lead with the key capability? All of these are messaging decisions that depend on you having pre-chosen whom you will target and how you will differentiate. And these messaging differences are testable.

Positioning needs to be owned by the CEO.

Because positioning is in essence an extremely strategic decision, it must be owned by the highest level of leadership.

The most likely candidate to spearhead positioning projects is the CMO — yet ultimately, it is the CEO’s responsibility to make these positioning decisions final and drive their actualization throughout the org.

Weaker CEOs will often attempt to pass off these extremely difficult decisions to others in the org. They’ll often rationalize their abdication of leadership as “delegation.” However, this is not something that can be handed off. If the CEO is not the one driving the positioning, the strategy will fail.

The homepage is your most important positioning asset.

When we began Fletch, we debated exactly how we would “package” positioning work.

We could focus on sales decks and sales narratives, similar to how April Dunford or Andy Raskin deliver their strategy work.

Our long term vision was to help companies determine their positioning strategy and then aid in its execution across all their assets. But ultimately as a two person consultancy, we realized this would be biting off way more than we could chew.

Eventually, we decided to anchor our delivery solely on homepages for two primary reasons:

1. The homepage is incredibly accessible.

Most positioning strategies live in a “positioning brief” hidden deep in the marketing org’s Google Drive folder. This inaccessibility all but guarantees that other teams outside marketing will not transmit the ideas into their own internal or customer-facing communication.

Additionally, positioning work that finds its home in a sales deck or sales narrative is equally siloed from the rest of the org, making it much harder to guarantee widespread adoption.

Conversely, the homepage is just one URL click away.

Investors can see it, customers can see it, and most importantly, your employees can see it with virtually no effort — which helps keep everyone aligned.

2. Homepages are written with customer-facing language (and thus easier to translate).

Another issue with many positioning briefs is that the strategic language is often wooden, stilted, and devoid of context. There’s usually too much room for interpretation in applying the messages across channels and departments.

As a result, you can get “positioning drift” (i.e. teams making changes to your strategy—often without realizing it—for the sake of “better copy.”)

“We didn’t like how that sounded, so we changed the wording.”

“We just punched up the language.”

“We thought saying it this way was catchier.”

The problem is these types of “creative changes” often contain substantive changes in whom you are targeting, how you’re differentiated, and what value you’re providing.

Listen how your sales teams pitch your product on demos and compare it to how your marketers talk about the product in their ads. Then take a peek into your onboarding and check how the company is being explained to new employees. Finish out your journey by sitting in on a call with the board to see how your CEO positions the company.

If you’re like the vast majority of organizations, you will find massive discrepancies in each of these contexts.

It’s very possible (and likely) that each team was distributed the same “positioning brief,” “brand strategy,” or “communication guidelines.” And yet because these documents are “pre-translation” (i.e. they haven’t been written in a way that’s meant for public consumption), teams will take heavy liberties when translating them to their differing contexts.

If you’re able to do that initial translation from strategy to a public homepage, everyone gets a workable frame of reference that makes it significantly easier to translate for their given contexts.

Choosing your target customer segment

There are two main decisions that comprise your positioning strategy:

Choosing your target customer segment (the focus of this piece)

Choosing your differentiation (the focus of part two)

If the first decision to make revolves around choosing a target customer segment… we need to ask: “What is a segment?”

We’ll use business software for this example.

If you take the total population of working people, you could consider that the total market for business software. However, no product or marketing strategy can serve (or reach) all working people.

So companies selling business software must divide this large group into smaller segments in order to create meaningful products and effective distribution strategies.

Segments can be large or small — from hundreds of millions of individual users (as with Microsoft 365) to dozens of world governments (as with Palantir).

Any time you are using some criteria to break up a large pie into smaller pieces, you are doing segmentation. But there are some ways to segment that are more useful than others.

Many companies will build target segments around firmographics (i.e. “our target segment is logistics companies with 500-1000 employees doing $75 million to $250 million in revenue per year.”)

The issue with building target segments based purely on firmographics is that the actual workers in these disparate companies are not necessarily doing the same activities that would be supported by your business software (despite the companies sharing similar characteristics.)

Remember… B2B software exists to help workers do their actual work.

Imagine you make software that measures the carbon footprint of a given company. You may reason that logistics companies of a certain size would be interested in this product. And yet, some logistics companies will have green energy initiatives or government pressure to calculate their carbon footprint… and others won’t.

Simply being a logistics company with certain firmographic characteristics does not guarantee that they will be doing this specific activity that would be supported by your carbon-footprint-measuring product. The firmographic segmentation is thus a very blunt instrument in gauging whether or not companies would be a good fit.

So if firmographics aren’t the best way to segment a market (because they don’t guarantee that the workers in a company will actually need your software to do their work), then what is a better alternative?

The somewhat obvious answer is that it’s far more effective (and expedient) to build segments around the actual work that is being done.

Use case-based segments

Segmenting a market by “activities” or “workflows” is what we call “use case-based segmentation.”

I’ll use a simple example with a company called SmallPDF. They launched with a simple web app that allowed customers to take a large PDF and shrink it to a more manageable file size without losing too much fidelity.

You could make assumptions about which size of company, headcount, revenue, etc. would be best suited for this product — but it’s for more effective to begin with the segment of users that want to “shrink their PDFs.”

The use case-based segment for SmallPDF would thus be: “people who are trying to shrink their PDFs.”

SmallPDF used an SEO-driven strategy to capture people from a wide set of company types who were Googling “shrink my pdf,” all but guaranteeing that those clicking would become users of the product. (Fun fact: their website gets around 45M visits per month).

Your target segment must include a use case if you want your distribution and product strategy to be effective.

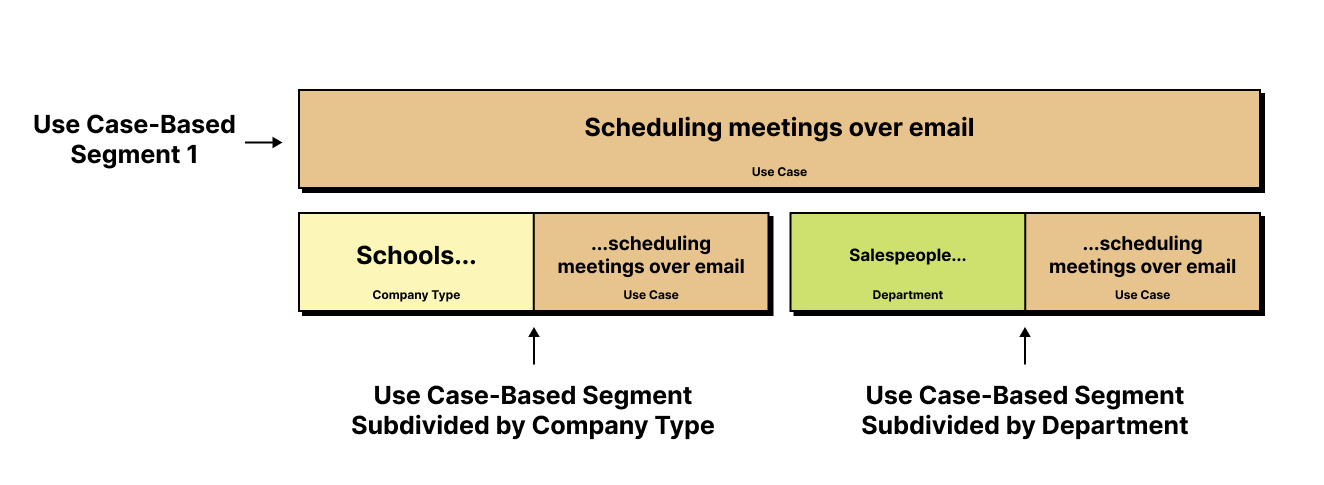

If you start with this broad segment of people doing the activity that is best served by your product (i.e. the use case-based segment), you may want to further sub-divide this segment depending on the size of your go-to-market muscle.

For example, Slack’s broadest “use case” is “internal business communication.” They have estimated that there are roughly 1 billion knowledge workers engaging in this activity who could be potential users of Slack.

As a fledgling startup, Slack did not have the resources to go after this massive segment all at once. So they layered on additional segmentation elements to shrink the market to a more manageable segment that could be reached given their smaller resources.

They went to market for that same use case (i.e. “internal business communication”) but segmented even further to engineering and software development teams who were already accustomed to using tools like IRC. This allowed them to focus their efforts on a segment they could more reasonably expect to reach.

Any “vertical” (i.e. industry-focused) positioning approaches begin with a wide use case and then layer on an industry focus to further segment. Square solves the use case of facilitating and managing sales transactions using a card reader (an industry-agnostic use case). Toast solves this same use case… but specifically for restaurants.

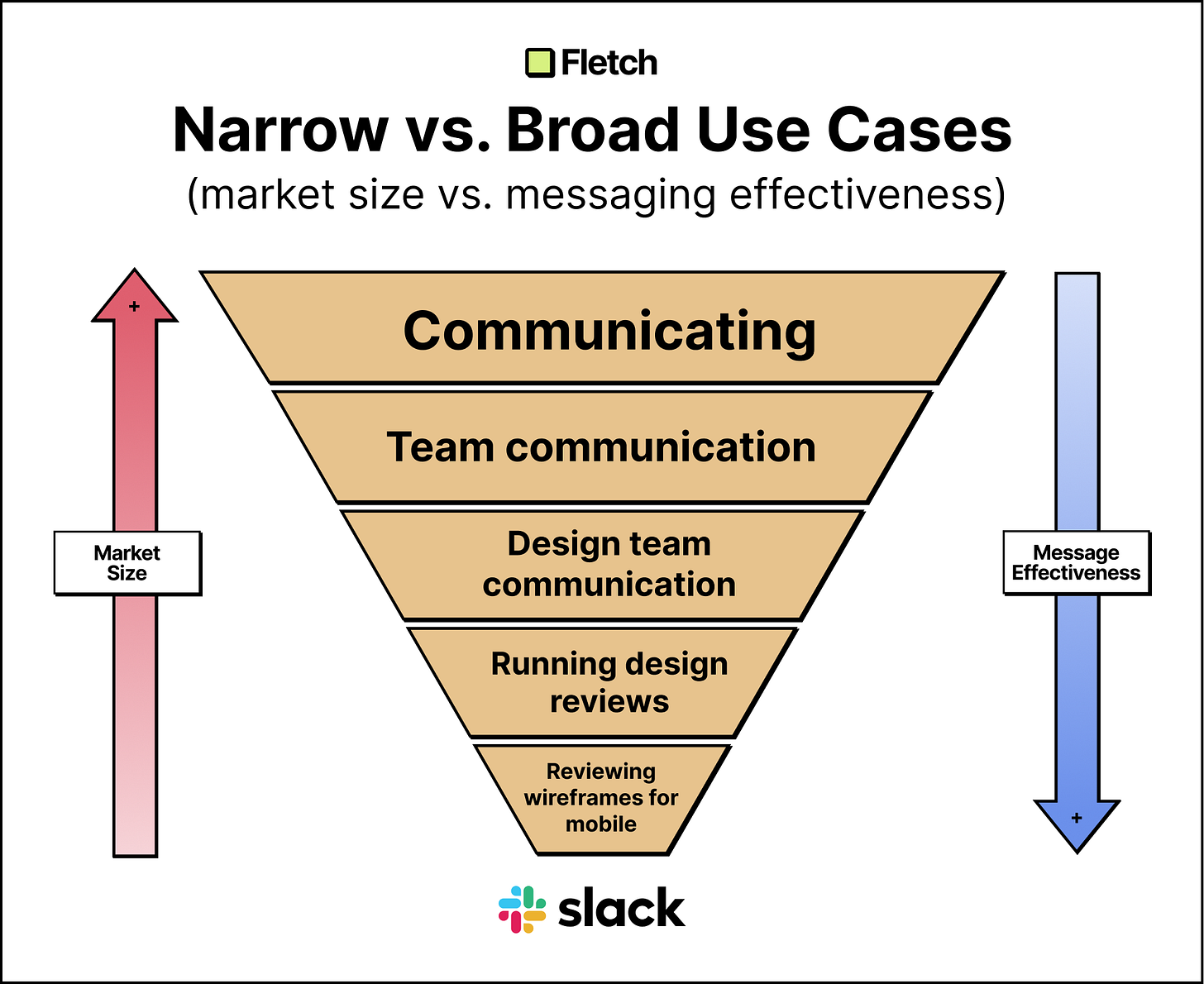

The “width” of use cases

Use cases have varying degrees of specificity and can be conceptualized in terms of “width.” For example, you might have an extremely narrow use case that is served by your product (i.e. “schedule a LinkedIn post”) or a very wide use case (”do ABM”).

The wider the use case, the larger the market size… but the less effective your messaging will be. With wider use cases, there are more moving parts and a greater number of involved parties who own different aspects of the workflow. This makes finding unified messaging that is sharp enough to be compelling for every single audience extremely difficult.

Additionally, wide use cases like “doing ABM” often have varying definitions depending on who you’re targeting. And so with broad use cases, you introduce ambiguity that inhibits understanding and word of mouth.

On the flip side, very narrow use cases can have extremely powerful messages — but may have smaller market sizes. For example, the product RB2B launched with one specific use case: “See who is on your website at any given moment.” The product lets you install a script that will give a best guess of your anonymous visitors, and then push their LinkedIn profiles to Slack. The company is still early and is doing roughly $4M ARR at the time of this writing. How large is the market for this very narrow use case? Time will tell. But it is likely much smaller than the market for products with use cases like: “doing ABM.”

Choosing the width and scope of your use case-based segment depends a lot on your ability to effectively execute a successful GTM plan. The wider the use case, the more difficulty you’ll face as a smaller company in reaching the larger market. The narrower the use case, the higher your chances of success… but the smaller the total market opportunity.

Use cases vs. Jobs-to-be-Done (JTBD)

If you’ve been around the block in product management, you’ll likely notice similarities with how we speak of “use cases” and the theory of Jobs-to-be-Done.

My co-founder Robert Kaminski and I debated simply adopting the existing language of jobs-to-be-done and incorporating it directly into our positioning model.

The issue is that there are two opposing schools of thought related to JTBD that would create too much confusion.

One camp (led by Bob Moesta) conceptualizes jobs-to-be-done as desired outcomes. The other side (led by Tony Ulwick) refers to jobs-to-be-done as functional activities.

The way we use “use case” is much closer to Tony Ulwick’s definition. However, we believe by simply saying “you should segment by the job-to-be-done” would lead to confusion for all those who follow Bob’s approach. When we attempted to use these terms in the past, people would often say “we are focusing on the Job of ‘increasing revenue.’” This, to us, is a nonsensical statement, because of the points made above about workers buying software to support functional activities.

That is not to say that outcomes do not play a role in our model — they absolutely do. However, unlike functional activities, they are not an effective way to segment for B2B.

Use cases vs. product categories

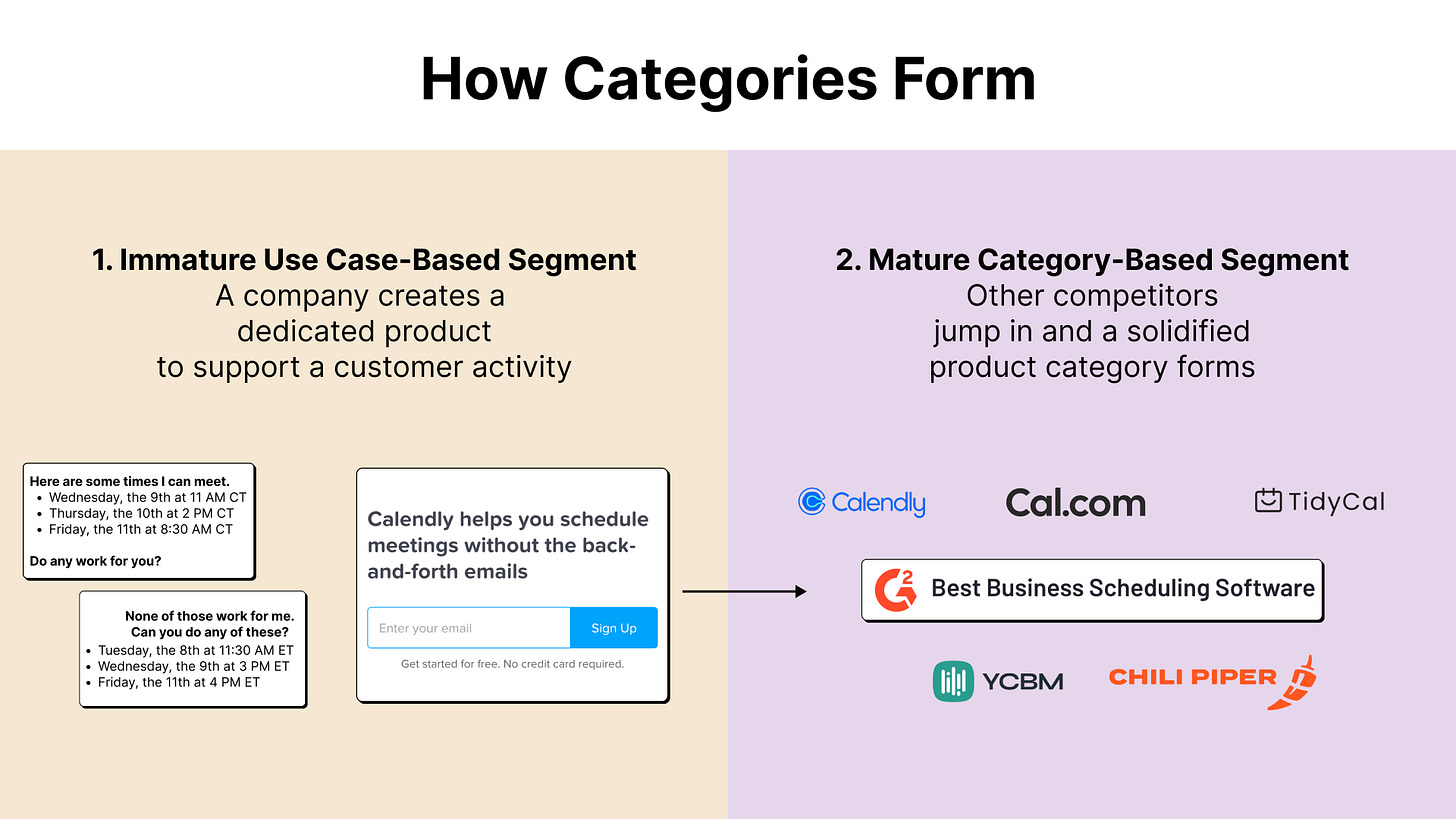

Use cases exist on a spectrum of maturity. They begin as a set of activities being performed by individuals who don’t even conceptualize them as a workflow of any kind.

Let’s use the example of Calendly.

People took it as a given that the way you coordinate a meeting between two people is by sending emails back and forth suggesting times until a mutually beneficial slot could be reached. This “use case” of “scheduling meetings over email” was very immature in 2013 when Calendly launched.

That is not to say that nobody was doing this activity. On the contrary, it was happening every single day in millions of businesses around the world.

It was immature in the sense that nobody conceptualized it as a “scheduling workflow” or even an activity worth a second thought — it was just an unnamed part of doing business.

Calendly launched with the goal of making this specific activity less painful by allowing others to book directly on your calendar based on what open availability existed.

Over time as Calendly started to gain users and revenue, other companies saw an opportunity to jump in and compete for this same use case-based segment. A flurry of alternatives (Cal.com, ChiliPiper, etc.) came onto the scene and suddenly a new category of software became to emerge: “scheduling tools.”

You now can visit G2, Capterra, Gartner, etc. and see the total market map of software that fall in the category of “business scheduling tools” and how they compare to one another.

To reach what is hopefully an obvious conclusion at this point: product categories (like “Business Scheduling Tools”) are simply mature use cases.

Once a set of activities receives a name and is served by a specific type of software vendors with comparable feature-sets… you have witnessed the transformation from an immature use case to a mature use case embodied in a product category.

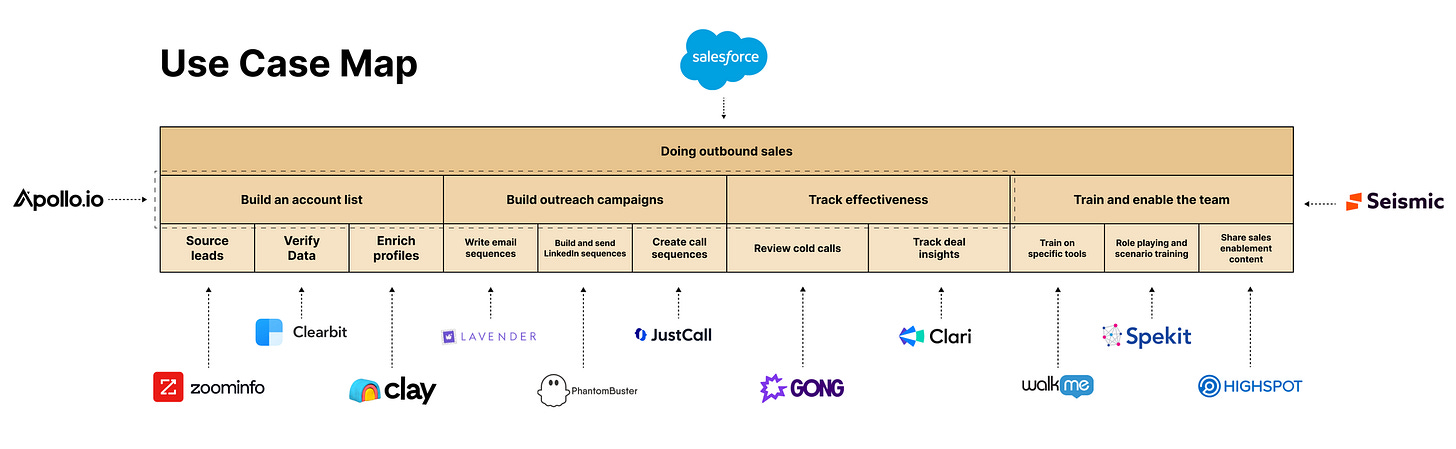

The same exact pattern has played out with all the software categories you know and love. Consider sales engagement tools:

Salespeople cold called and cold emailed new businesses with specific regularity and cadences

These tasks begin to be grouped into workflows (i.e. “outbound sales” or “sales engagement”)

Companies like Apollo, Lemlist, Salesloft, Outreach, etc. created software to support this entire workflow, which developed into a new category of software (i.e. “Sales Engagement Tools”)

Additionally, because product categories are “hardened,” mature use cases, they contain a built-in market segment.

As an example, one can speak of the “market” for CRMs as being quantifiably valued at ~$100 billion in 2024.

A CRM company saying, “our target segment is companies shopping for CRMs” is comparable to SmallPDF saying, “our target segment is people who are trying to shrink their PDFs.” The first use case (customer relationship management) is mature, has been named, and now has a dedicated product category for it. The latter use case was immature and did not (yet) have a named category associated with it… yet both are use case-based segments at heart.

This post may be cut off by your email provider. You can read the full version here.

Choosing between immature and mature use case-based segments

As mentioned earlier, positioning strategies require making two distinct decisions:

Choosing your target segment

Choosing your differentiation

I made the argument that target segments must include use cases in order to be effectively marketable and that use cases fall on a spectrum from immature (i.e. activities being performed with out a dedicated product category) to mature (i.e. having a dedicated product category that serves them).

In order to position, you as a company must determine which opportunity you want to pursue:

Will you focus on the immature market (i.e. people doing an activity)?

Or will you focus on the mature market (i.e. people shopping for a specific product category)?

There are pros and cons of choosing an immature use case-based segment:

Pro: The immature segment usually has less competition. By nature of being “immature,” bigger incumbents likely haven’t entered the fray just yet. This can give you a large head start and a chance to become the de-facto solution for a given workflow (assuming you’re able to effectively dominate the use case-based segment).

Con: This method usually takes much longer to actualize. There’s usually a decent amount of education required (i.e. you may need to help customers understand that certain activities do belong together in a unified workflow, as HubSpot did with the concept of “inbound marketing”).

There are also pros and cons of choosing a mature use case-based segment that has a dedicated product category:

Pro: There is almost no education needed. You can simply enter the conversation and show how you’re different (and provided you are differentiated in a meaningful way, you can quickly gain marketshare).

Con: You need real, meaningful differentiation. Usually what companies think is powerful differentiation (i.e. we are faster, we have better customer service, etc.) actually doesn’t matter enough for customers to switch from their current vendor.

Remember… it’s a choice!

When we consult with companies, we are often asked “how do we determine which segment to choose?”

Welcome to the wonderful world of entrepreneurship.

There is no science that will help you make this decision. You can take in as much data, analysis, and research as you want… but at the end of the day, you are still making bets about the future.

Will we be able to effectively reach (and dominate) this segment?

Will our differentiation be strong enough to convince people to leave the market leader?

Will people still be performing these activities in five years?

All of these are unanswerable questions. They can only be bet on, in the same way people bet on the latest American election or the result of a sporting event.

As mentioned above, you will need different positioning strategies for each different segment. However, companies have finite resources and must prioritize where they are going to focus their energy.

If you’re Salesforce, you can likely go after both immature and mature markets simultaneously with massive amounts of GTM and product muscle. If you’re an early stage startup, you will likely need to choose one or the other.

Tools for the job

Let’s bridge the gap from theory to practice. In our consulting practice, we have created several assets that you can use to help frame your decision-making.

We’ll begin with the use case map.

You can begin by listing the highest level use case of your product. This is the largest activity or workflow that your product can support end-to-end.

Then, we go down one row and break up that workflow into its component parts (i.e. sub-activities that map up the larger activity). From there you can subdivide as far as you would like by adding more rows and more sub-activities.

Each box represents a distinct market segment. The wider segments in higher rows have a larger market opportunity (but more competition and more messaging ambiguity). The more narrow segments in lower rows are smaller market opportunity, but easier to reach with stronger messaging and product satisfaction.

You can see here a completed use case map showing how different sales tech tools primarily focus on different segments.

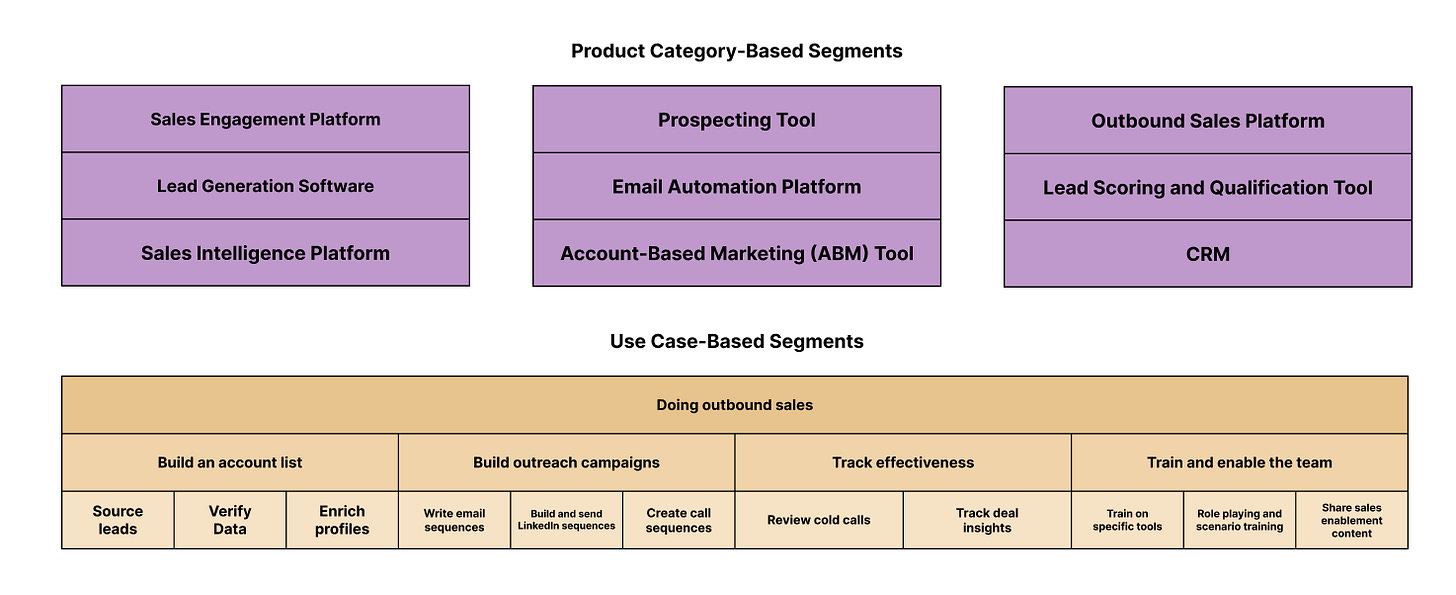

We often suggest that founders first complete a use case map, and then also list all the different categories that fit their product.

All of the squares (both brown and purple) represent potential target market segments that could be the focus of your positioning strategy.

From here, you can try to narrow down by removing categories that don’t quite fit what you do or use cases that don’t match your criteria (i.e. use case segments that are too large for you to dominate, or too small to meet your growth goals.)

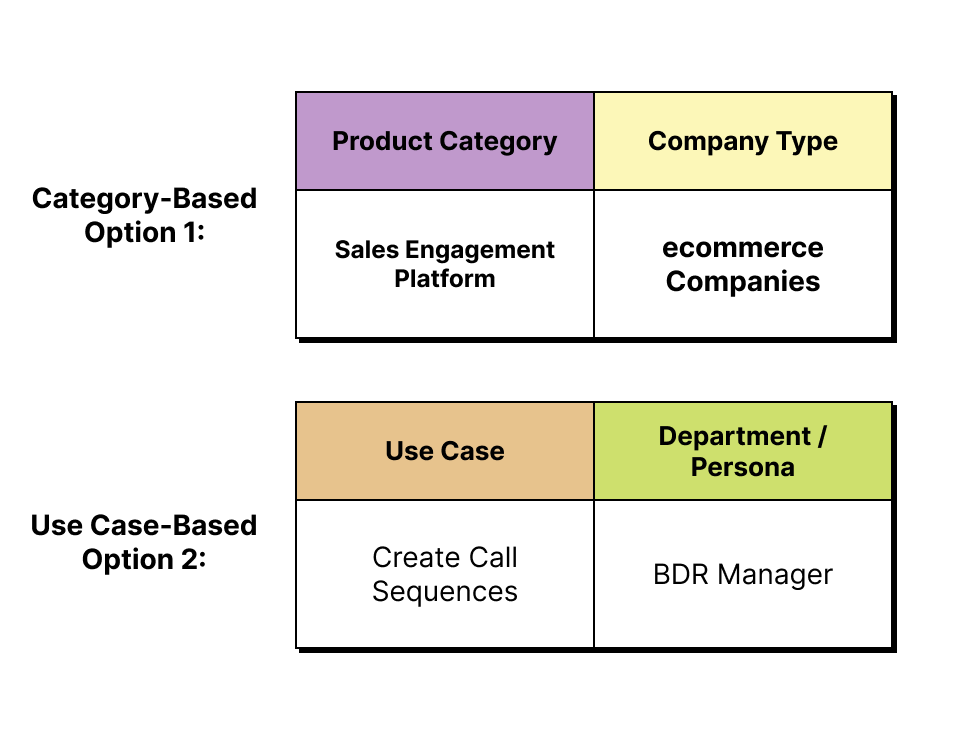

Once you’ve narrowed down your list, we suggest layering on additional segmentation in order to further dial in your ICP (”ideal customer profile”).

These might include company details or department/persona details, as demonstrated below:

What comes next

If you’ve been following along and attempting these exercises with your own company, so far you should have:

Chosen a target segment (either an immature segment based on a use case or a mature segment based on a product category)

Further refined this target segment with additional firmographic and departmental details

Your next steps will be to:

Choose a competitive alternative (and map out its shortcomings)

Choose your differentiation (either binary differentiation or differentiation by degree)

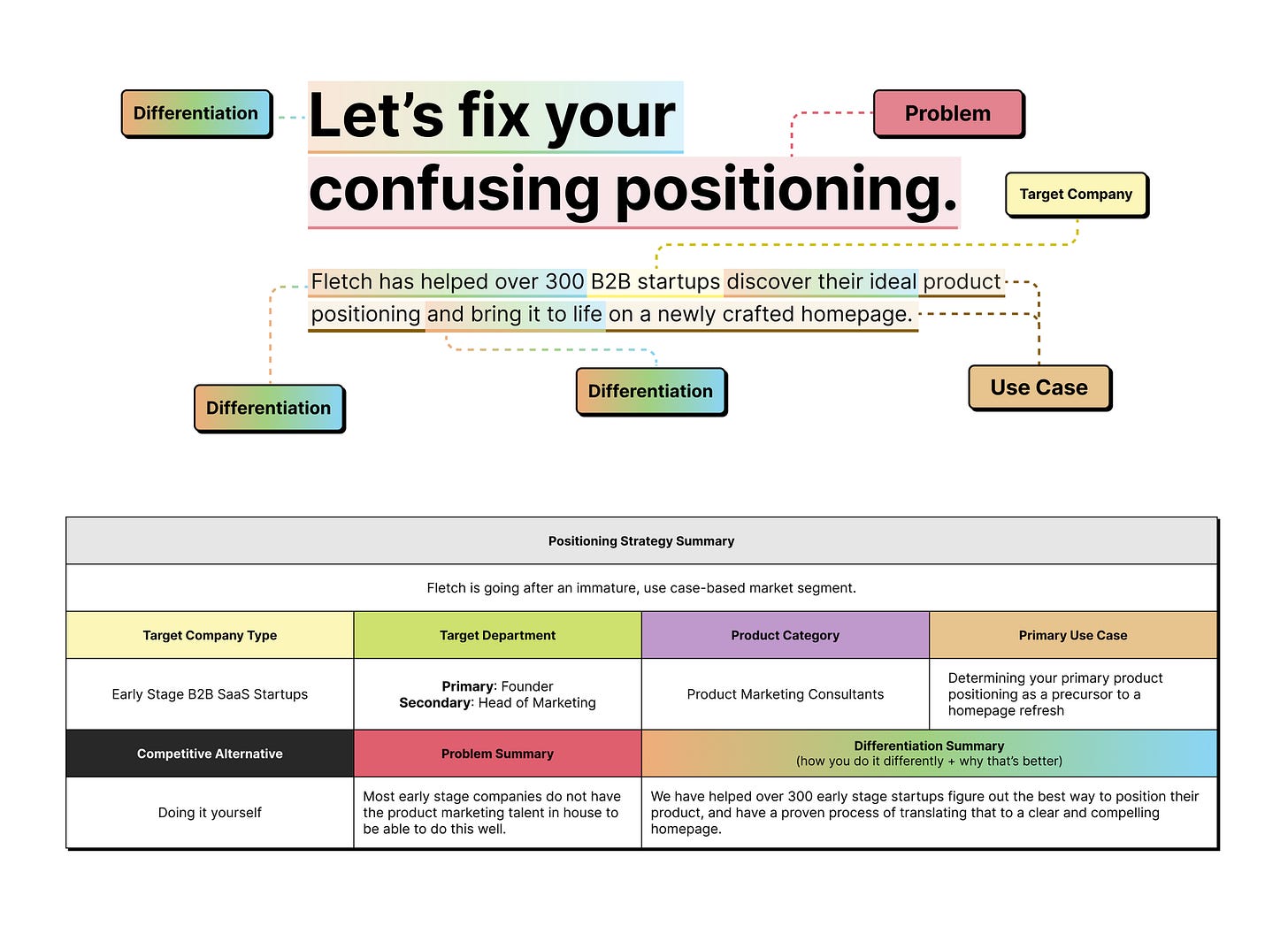

These will eventually come together in the Positioning Canvas (I have filled it out using my own consultancy’s positioning strategy below). Stay tuned for part two—and subscribe to get it sent straight to your inbox.

This article was originally published here.

It sounds like you're working on a strategic positioning framework, perhaps for a business or consultancy. The Positioning Canvas is a great tool to define and clarify your brand's unique space in the market. By outlining aspects like target audience, value proposition, and differentiation, it helps ensure your messaging resonates with the right people.

For part two, I imagine you'll go deeper into specific elements or perhaps give a detailed breakdown of how these pieces fit together to form a cohesive strategy.

The definitive product positioning framework helps businesses define how their product fits into the market and stands out from competitors. Part one likely covers the foundational elements, such as identifying your target audience, understanding customer needs, and assessing competitors. By clearly defining the product's unique value proposition, businesses can create messaging that resonates with the right audience and guides marketing strategies.